Ireland has been building its high-value bioeconomy ever since its 2018 National Policy Statement for the Bioeconomy (NPSB).

Things have moved speedily in the last year, with the release of Ireland’s first National Bioeconomy Action Plan 2023-2025.

Yet even in these early stages, Ireland’s bioeconomy policy has already been distinguished by an emphasis on scaling and marketing biobased products.

With three new funds focused on biobased scaling in the last year alone, Ireland is on track to addressing a major blockage of the EU bioeconomy where products are failing to transition from the lab to market quickly enough.

We look at what Ireland is doing to ensure innovative biobased ideas reach the industries where they are needed.

Three market-focused bioeconomy programmes in one year

Biobased R&D has been at an advanced stage for a long time in Europe. Yet getting biobased products to market has been a stumbling block that even EU bioeconomy policy has not overcome.

In the EU, the middle of the biobased R&D pipeline – the part where promising laboratory ideas get proven at commercial-scale production in demonstration plants – is suffering from a funding shortfall. This is a critical area of the biobased industry as most high value bioeconomy innovations still need to be tested at scale.

Things are different in Ireland, which has hit the ground running with a stress on marketing products alongside their research and innovation. Although its first national bioeconomy strategy was released only in late 2023, Ireland has already been focusing its efforts on bringing innovations to market through an emphasis on funding pilot and demonstration projects.

The latest funding call for the bioeconomy was the Shared Island Bioeconomy, launched in March 2024 with online applications closing June 7 2024. It offers €9m in seed funding and focuses on new sustainable industries around agriculture and marine resources.

The project has a political dimension too, encouraging collaborations between stakeholders across the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

The Shared Island Bioeconomy programme follows on from the Bioeconomy Demonstration Initiative Scheme, launched in August 2023, which was eligible for Irish SMEs, local and regional authorities, as well as community and local action groups. Both pilot schemes support the country’s Bioeconomy Action Plan of 2023-2025.

In January 2024, Ireland’s commitment to demonstrating biobased products was showcased through BioDirect, a national project led by Circular Bioeconomy Cluster South West and funded by InterTradeIreland, a body that aims to cultivate business networks on both sides of the Irish border.

BioDirect is run in collaboration with universities like Ulster and Munster Technological University. However, its driving purpose is to connect biobased producers with potential industrial customers within packaging, construction, textile, and agriculture.

The project involved a challenge that helped pick appropriate biobased solutions for the right industrial partner, aimed at cultivating awareness among existing businesses of the biobased solutions on offer.

Lisheen as a region to watch

Lisheen in County Tipperary is shaping up to become central to Ireland’s bioeconomy. The Irish government is providing €4.6 million through EnterpriseIreland’s Regional Economic Development Fund for the establishment of a Bioeconomy innovation and piloting facility there.

The Irish Bioeconomy Foundation already has their headquarters at Lisheen.

The new facility aims to allow industry, entrepreneurs and researchers to scale high value biobased technologies across industries like food ingredients, animal feed, pharmaceuticals, and biodegradable plastics.

Focus on building a demonstration hub in the earliest stages of its national bioeconomy policy is a strategic decision. Right now, a lack of piloting facilities across the EU is one of the main reasons preventing the industry from scaling in the region. Ireland appears to have learned from this by building in testing facilities even as in the earliest years of its bioeconomy stimulus.

Yet Ireland is not overlooking biobased product innovation in its rush to bring products to commercial readiness. The government is bringing academic groups on board, having awarded the Technological University of Shannon €1.25 million towards developing two bioeconomy demo sites, including one at Lisheen.

Regulation is driving up Irish demand for biobased goods

This market-focused nature of Ireland’s bioeconomy projects reflects increasing demand among companies in Ireland for commercial biobased solutions. Driving this demand is a plethora of climate laws that Irish companies will soon have to comply with.

The country’s Climate Action and Low Carbon Development signed in 2021 committed Ireland to a legally binding path to net zero emissions no later than 2050 and a 51% reduction in emissions by 2030.

Ireland’s membership in the European Union is also pushing companies to look for lower carbon solutions in their manufacturing processes. One EU climate law that Irish businesses are preparing for is the EU Emissions Trading Scheme, which will be expanded to companies in construction, road transport and other sectors in 2027. Under the law the companies in the applicable sectors must reduce emissions through voluntary actions.

There is also the EU Green Claims Directive. Under the directive, aimed at clamping down on greenwashing, companies will have to ensure their products are labelled with reliable claims about their environmental impact that are backed by evidence. The laws are expected to apply from 2026 and non-compliance could result in penalties tied to annual turnover of the companies.

Then there is Ireland’s agricultural industry, an immense employer and economic actor that accounts for around 33% of its national greenhouse gas emissions, mainly from meat and dairy. Agri-food companies will likely need to turn to biobased inputs to reduce emissions from fossil-based inputs like fertiliser in a bid to maintain productivity while meeting national and international targets for air quality, water quality, and biodiversity.

600 companies and counting

There is a growing network of home-grown biobased companies ready to fulfil this rising demand for lower carbon solutions.

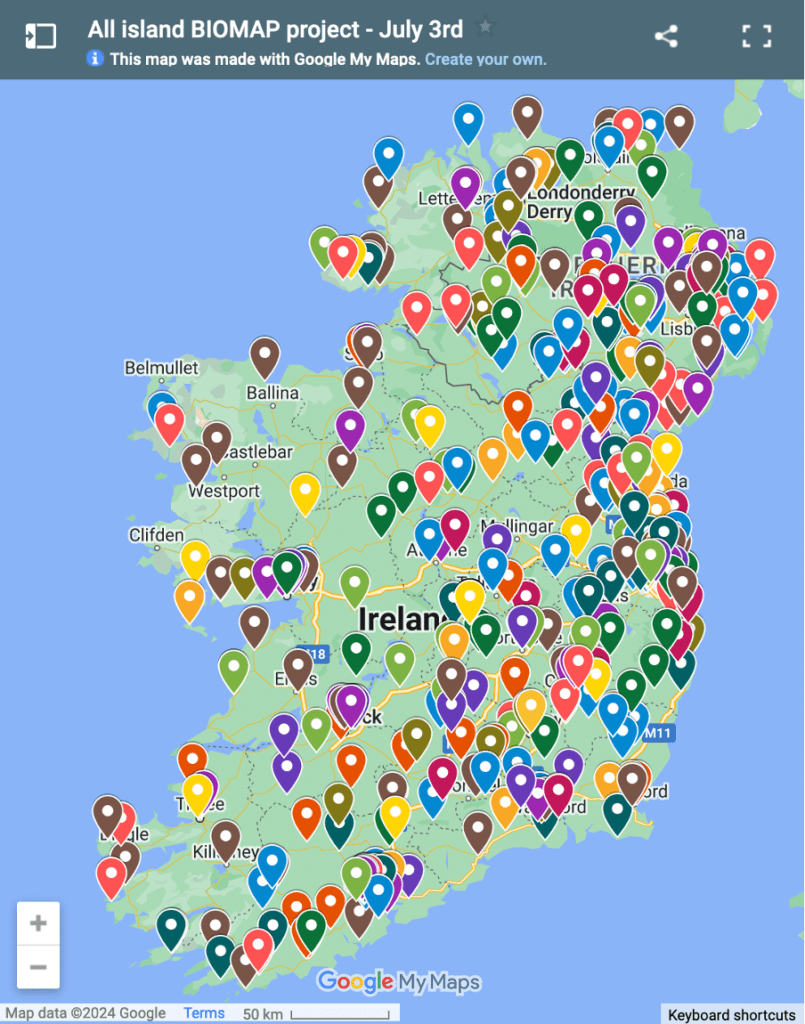

The map below created by the Irish Bioeconomy Foundation shows how dense the island is with companies involved in biobased value chains. So far, its BioMap project has identified almost 600 companies.

Tracking the number of companies relevant to the biobased supply chain is not just a marketing exercise for Ireland’s bioeconomy. It also plays an important practical role in scaling up biobased value chains.

The waste streams of one industry may be valuable feedstock for other industries, but knowing who needs what and who can provide it at cost is a coordination problem that the foundation’s mapping exercise is geared to solving.

Connecting companies that could benefit from each other is a vital part of the Irish Bioeconomy Foundation’s work. As the foundation adds more companies to the map, it makes it likelier that biobased companies in need of collaborative ties can find business partners quicker.

Public funding for risky enterprises

There are still hurdles to overcome in achieving an Irish bioeconomy that can support both decarbonisation as well as rural employment.

Irish biobased businesses today note there are still gaps in policies. In a criticism that echoes those made by bioeconomy actors around the world, many Irish biobased businesses want more government subsidies and feed-in tariffs for high-risk bioeconomy startups. This is especially in the early stages before commercial viability.

Public funding is needed where biobased goods are competing with older industries like oil or concrete which have established markets and economies of scale on their side.

Regulations must match bioeconomy ambitions

Businesses also call for updated regulations across sectors that allows for the use of biobased resources in construction. For example, there are limits on the height of buildings made from biological resources. These health and safety regulations do not necessarily reflect the technological readiness of biobased building materials.

A Bioecnomy Implementation Group set up to put Ireland’s 2018 policy statement into action looked at regulatory barriers to bioeconomy growth. One of the concerns they identified relate to the raw materials of the bioeconomy. The group pointed to weaknesses in waste legislation, arguing there was a need for criteria that picks out agricultural and other bio-waste streams that could be re-directed towards bio-manufacturing.

Bio-based producers need the government to re-define ‘waste’, which are often valuable products in the bioeconomy. Re-labelling this as potential raw material could make it easier for companies producing to sell their unwanted sidestreams onto producers that can valorise them.

Reclassification of waste as raw materials is not just an exercise in semantics – it can make a huge difference to the size of Ireland’s circular and bio based feedstock base.

For example, Irish law currently classifies topsoil from housing developments as waste. Any producer wanting to valorise it must apply for the product to get officially reclass as ‘by-product’. This can take months, putting off developers from selling the soil since storage has to be organised for it while the paperwork is being conducted.

Similarly, legal classifications pose barriers to biobased producers wanting to valorise oyster shells from mass mortalities of oyster beds. Oyster shells contain valuable compounds like calcium carbonate, usable for design and construction, and chitin, which holds biochemical applications across packaging and beauty industries.

Right now, there is legal ambiguity over whether waste shells are animal byproducts or not, which determines the kinds of industrial applications they can be used for.

Another problem is that current laws restrict the usage of anything classed as waste materials often for health and safety reasons. This limits the pool of raw materials that bio-manufacturers can work with.

Ireland has already made inroads into the biggest problem facing the European bioeconomy – a lack of biobased piloting facilities that get promising promises to the wider market. If producers are able to use these facilities to show their commercial viability, lawmakers must uphold their end of the bargain with regulatory changes that allow them to more easily scale operations.